Yes, and...

Taking a deeper look at LGBTQ+ book deals in Children's and YA

Happy New Year, Substack! Can I still say that, here in the third week of January? For many academics, the month of January gets gobbled up by the start of a new semester. This spring, I’m so delighted to be teaching a course on Young Adult Literature. This is a new class for me, and a new interest area—I’ve been reading as widely in the history of the genre as possible, working to familiarize myself with current and historical markets, and keeping abreast on current news.

This is one reason why I, like many of you, became hyper-focused on Surina Venkat’s report in The Hill, “Trump’s return chills embattled LGBTQ book industry: ‘They’re stepping back.’” The headline is general, but the article is much more specific: children’s and YA publishing. Venkat reports “lower sales numbers amid book bans, as well as the administration’s targeting of diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) and pre-occupation with “radical indoctrination” in K-12 schools.” Because YA and children’s are powered by institutional accounts (I.e., schools and libraries), any difficulty faced by those institutions becomes a challenge to publishers upstream.

I am entirely sympathetic with the article’s premise, and I had good reason to suspect that it’s accurate. Over the past few years, I’ve worked with students at Temple University (my employer, whose views are not necessarily expressed in this post) on a grant funded by the Mellon Foundation (see above, re: views) to study national trends in book banning. During that time, we talked with agents and editors who work on children’s and YA lit, and heard similar stories of scaling back, a chilling effect at the national level. I was thrilled to click on the link to the piece at The Hill, hoping I’d finally read a piece of deeply-researched reporting that would contextualize what I’d been hearing from friends and acquaintances in the industry.

While the piece was helpful and interesting, very usefully demonstrating the industry-wide effects of book bans beyond those felt by single authors, I found its evidence patchy. The piece quoted three agents: two said they’d had a client whose work was rejected on these grounds, and the third had heard of others who experienced rejection, though she and her clients had not.

Again: I believe that this is happening, and I believe that this is bad. But two stories and some hearsay do not make a trend. And this story is too important to rely on vibes alone.

Whenever I hear statements such as these, particularly regarding representation, I always imagine The Skeptic. He’s usually a well-educated white man, probably with an M.B.A. He might call himself a “social liberal but fiscal conservative.” He wants to help, he assures me— but the numbers just don’t support it. Maybe he doesn’t believe there’s a problem in the first place. This is the guy I’m trying to convince. This might be a fool’s errand, and maybe I’m naïve, but I believe that minds and attitudes and beliefs can change when we approach one another in good faith. (I have to believe that— fundamentally, in my soul.)

So here’s my data-driven follow-up to the piece in The Hill, in hopes of convincing the guy in the boardroom, with some receipts.

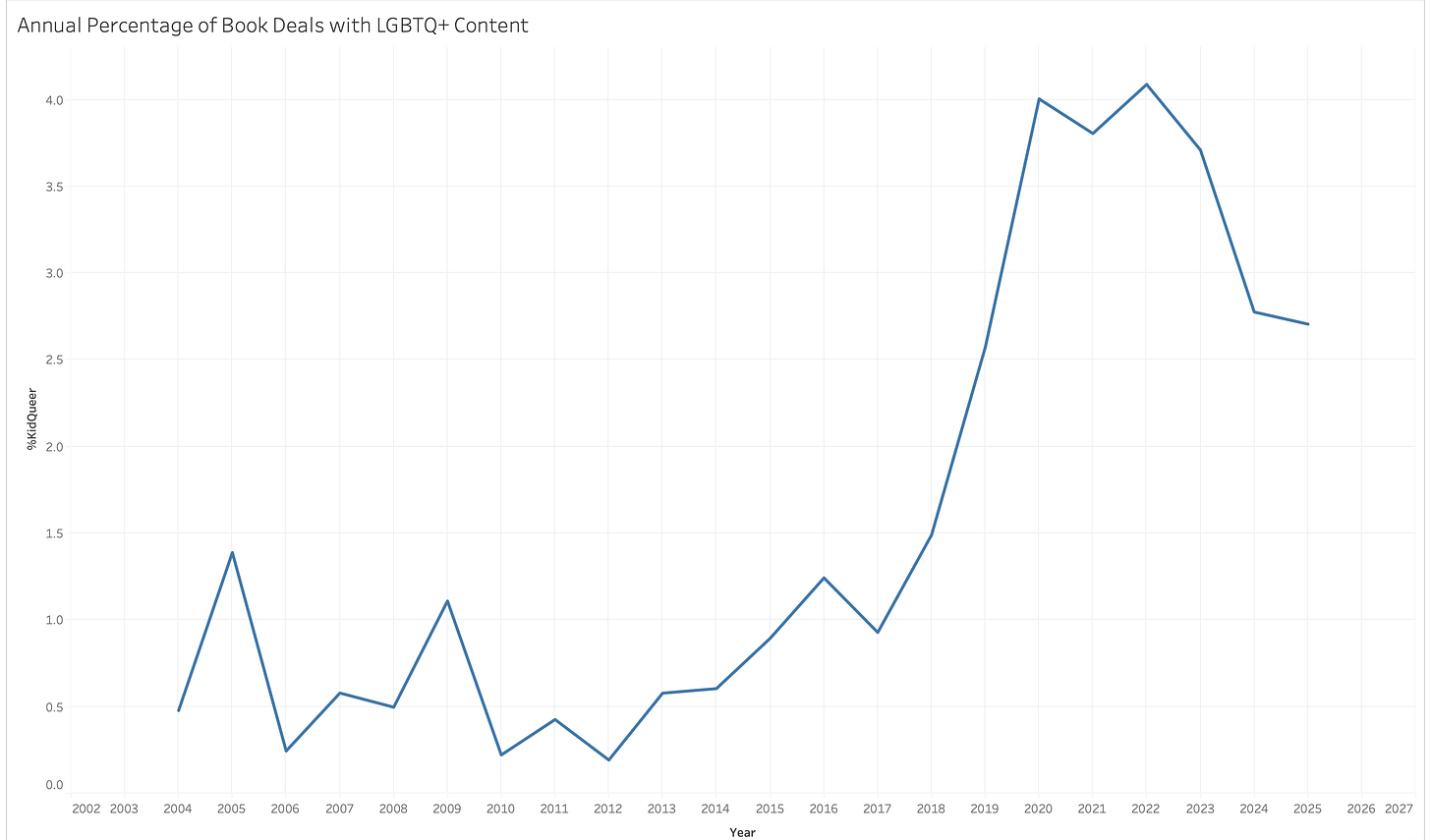

Since the argument of the piece had less to do with book sales than book acquisitions, I turned to Pub Marketplace to get a sense of the pipeline. (Methods in the footnotes.1) In terms of the marketplace for Children’s and YA Lit featuring queer content, the active market is relatively recent. Looking at the data since 2004, I see four main periods of acquisitions in Children’s/YA LGBTQ+. Books. (I’m going to use the clunky term “LGBTQ+YA” for the remainder of this post.)

Period 1: Forming. Prior to 2015, there is no real cohesive LGBTQ+YA market to speak of. A few deals are posted each year, but not in significant numbers. To be sure, there are many Children’s and YA books that feature LGBTQ+ characters— I’m teaching Boy Meets Boy this semester, for example, which was published in 2005. And there are just as many queer-coded books that would not register LGBTQ+ themes at the level of a deal announcement.

Period 2: Building. Starting around 2015, LGBTQ+YA begins gaining steam. 2016 is the first year in which LGBTQ+YA reaches more than 1% of total KidLit deals.

Period 3: Surging. And then, in 2019, it explodes. The number of acquisitions announced doubles, and kicks of a period of unprecedented market growth. Between 2018-2023, LGBTQ+YA reached about 4% of the total KidLit market. This, despite the fact that this newest wave of book bans targeting LGBTQ+YA kicked off around 2020. (PEN America began tracking in 2021.) Even while book challenges were surging, the LGBTQ+YA market remained robust.

Period 4. Cooling. But, in 2024, the market began to cool. In 2024, the number of deals announced for LGBTQ+YA decreased by a percentage point, and did not regain any ground in the following year. The number of books acquired in 2024 and 2025 looked more like 2019, at the very beginning of the YA surge, rather than its peak in 2021/2022 . I don’t need to remind you what happened in fall of 2024.

Periods 3 and 4 are the most interesting to me, suggesting that the situation might be a bit more complicated than was reported. Why is it that, just as book challenges are at their most virulent, the market for LGBTQ+YA is equally strong? Of course, the data don’t have the answer to this, so allow me to speculate wildly!

The first is that we had no idea if, and for how long, book challenges would continue— and, in my opinion, we underestimated the organization of challengers. Perhaps it wasn’t taken seriously enough as a force that could impact the market? Or, second, perhaps publishing responded as many readers did— by doubling down on the right to read widely and freely, to represent the fullness of childhood and young adulthood in all its diversity, Moms for Liberty be damned. (Remember the “book bans are good for sales” narrative?) Regardless of the initial response, it takes some time for the squeeze placed on institutional accounts to likewise squeeze suppliers (publishers). We shouldn’t expect to see an immediate effect. With the second Trump election, though, it became clear that the challengers would continue to be emboldened, that so-called parents rights had moved to the White House.

I will, however, offer a note of caution: the past two years have seen a decrease in acquisitions that is not random, statistically. However, I would note that the percentage of LGBTQ+YA is still greater than it had been in Periods 1 and 2. We’ve receded to 2019 levels, not to 2009 levels. And don’t forget, publishing is both volatile and cyclical. These are only short-term changes; without the benefit of hindsight, we can’t call this a trend or a new period or a reversion: we can only remark that something seems to be happening.

Interestingly, we don’t see a comparable decrease in the Adult LGBTQ+ market. There has been greater variation in the Adult market, but likewise, we see a flourishing beginning around 2019 that remains consistent. LGBTQ+ Adult deals actually haven’t decreased, in terms of a percentage of total deals, since 2024. In other words, this phenomenon does seem to be localized in Children’s/YA. It’s not just Trump, in other words, as much as the combination of Trump plus book bans. There may be good incentive for YA authors to recategorize some of their books as “New Adult,” rather than risk this challenging market (and, incidentally, PM counts “New Adult” amongst Adult Fiction rather than Children’s), which would partly create this effect in the data.

But let’s set all of this aside for a moment. One reason why any decrease, no matter how minor, feels like a huge setback is because LGBTQ+ YA is so embattled to begin with— even before book challengers and even before Trump took office a second time.

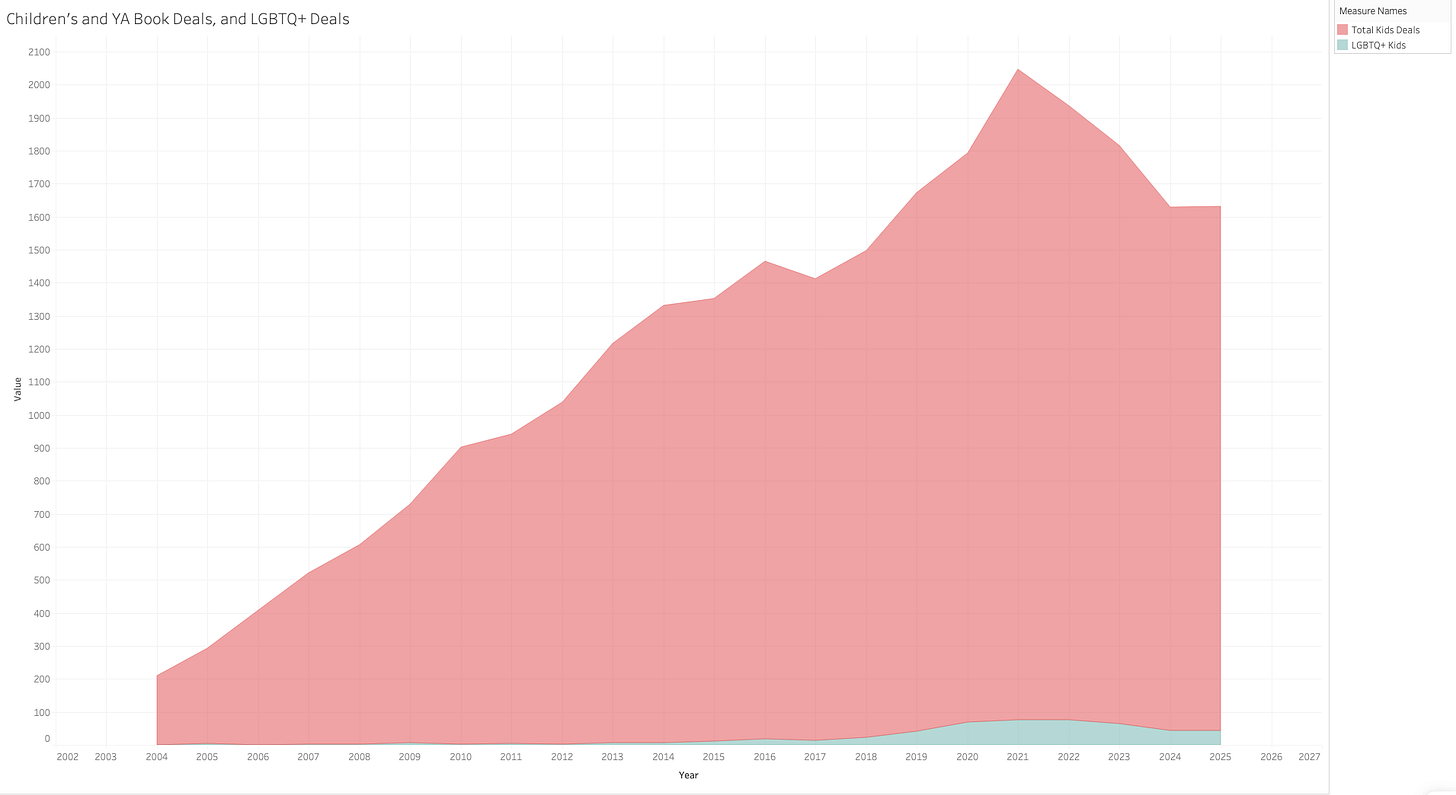

Increase or decrease in book deals aside, in absolute terms, we’re talking about a shockingly low number of books about LGBTQ+ children and young adults. Let me redraw the graph above to show exactly how few books we’re talking about.

See that little blue shaded area, at the bottom? That vanishingly small area that you may need to squint to see? That represents the number of book deals about LGBTQ+ children or young adults that have been published each year.

It’s not like “2019 levels” were good. It’s not as though “the surge” that I identified in book deals helped LGBTQ+ books and authors achieve anything close to representational parity. I don’t want to erase the activism that went into securing this small segment of the market— but I also don’t want to pretend that the situation was good, to begin with. That this was ever enough. (It wasn’t.)

So: where does this leave us? It leaves some more questions and some important context and additional complicating factors, but not terribly different conclusions than were reported in The Hill. In fact, despite these outstanding questions, the data support the headline almost verbatim: “Trump’s return chills embattled LGBTQ book industry.” Yes, this seems to be true, and the data show a decrease in acquisitions of books about LGBTQ+ children and young adults.

Still, even when they confirm our suspicions, I think supporting data like these are helpful when trying to get a sense of the problem(s), in all its complexities and reach. I also think it’s important, and strategic, to get a sense of the landscape in order to address the problem. (Or to convince skeptics that there’s a problem, in the first place.)

I’ll leave that to the professionals.

This is some quick and dirty data analysis: I ran a number of searches for “LGBT”, “queer”, “trans”, and every word in the acronym with variations, and — after cleaning lightly— added these up to get a total. To obtain percentages, I compared these totals to the total number of deals in the “Children’s” category on PM. Likewise with “Fiction” (Adult). This does not include Adult Nonfiction.

I’m aware that these numbers are certainly missing a lot! And this is an imperfect way to search for LGBTQ+ content. But I don’t think I’m missing enough to change the big-picture analysis.

It’s incredible you have the ability to do this with PM data!

Thank you for this! Did you include the word “sapphic” in your search, by chance? Also, I would posit that part of the drop in numbers is due to the shift away from LGBTQ+ “issues” being the focus of books and more towards characters just being LGBTQ+ without it being an issue—in other words, they were mainstreamed. A description might mention a teen who starts to have feelings for their best friend without naming the friend’s gender. And biographies of famous queer folk wouldn’t necessarily mention their queerness in a deal announcement description if it’s well known.

It would be interesting to look at the Stonewall and Lambda nominees/finalists and winners in the kids and YA categories and go find their deal announcements and see if the announcements used any of the keywords you used to search for them.