textCrunch, No. 3: Relative to what? On publishing industry demographic data

and getting more concrete with our critiques

Welcome back to textCrunch! And hello, new subscribers! I’m so happy to have you here. This is a quick post—I’m prepping a much larger deep dive into nonfiction data for May, for paid subscribers. Don’t miss it!

One of the drums I beat constantly is that there is a direct relationship between the demographics of the publishing industry (the people who make books) and the books that we read. This matters when it comes to who gets published, whose stories are told, who is (presumed to be) reading, and, consequently, who books are made for.

I certainly don’t need to tell you this, reader. If you’re interested in data and publishing, then you know the numbers. And you’ve read the dozens of think-pieces that are published every few years on the “unbearable whiteness” of publishing. But how white, exactly, is publishing? Relative to what?

This is a question that a Peer Reviewer has been pushing me to answer in my book manuscript.1 Is publishing whiter than the national population? Whiter than comparable professions? How white should we “expect” it to be, and how bad is the representation problem, exactly?

Initially, I found this question a bit tedious and, frankly, annoying. (Sorry, Reader 2, ily!) It seemed like an attempt to dismiss the problem of racism by nitpicking over stats. But then, after I whined about it to a few trusted friends and they reminded me that Peer Reviewers offer criticism in good faith and that it is the scholar’s responsibility to respond in kind, I admitted how useful this information would be, and that I should’ve started here. (Peer Review, like fact-checking, is a gift to us all.) And so, ego in check, I sat down to crunch the numbers.

Before we dive in! A quick event announcement: if you’re in or around New York, come see me chat with Isaac Fitzgerald, Randy Winston, and Kate Dwyer on Debut Novel 101 at McNally Jackson on April 16 at 6:30 pm! Grab your seat here. New York Mag officially placed the series in its coveted “highbrow-brilliant” quadrant (all thanks to Kate’s brilliance).

To start, I’m using the most recent Lee & Low Diversity Baseline 3.0 statistics on publishing industry demographics. I opted to use Lee & Low instead of the PW Salary Survey because it surveys a wider group of publishing professionals and because of the larger sample size. For the US Population, I relied on the US Census Bureau. Other relevant data sources noted below.

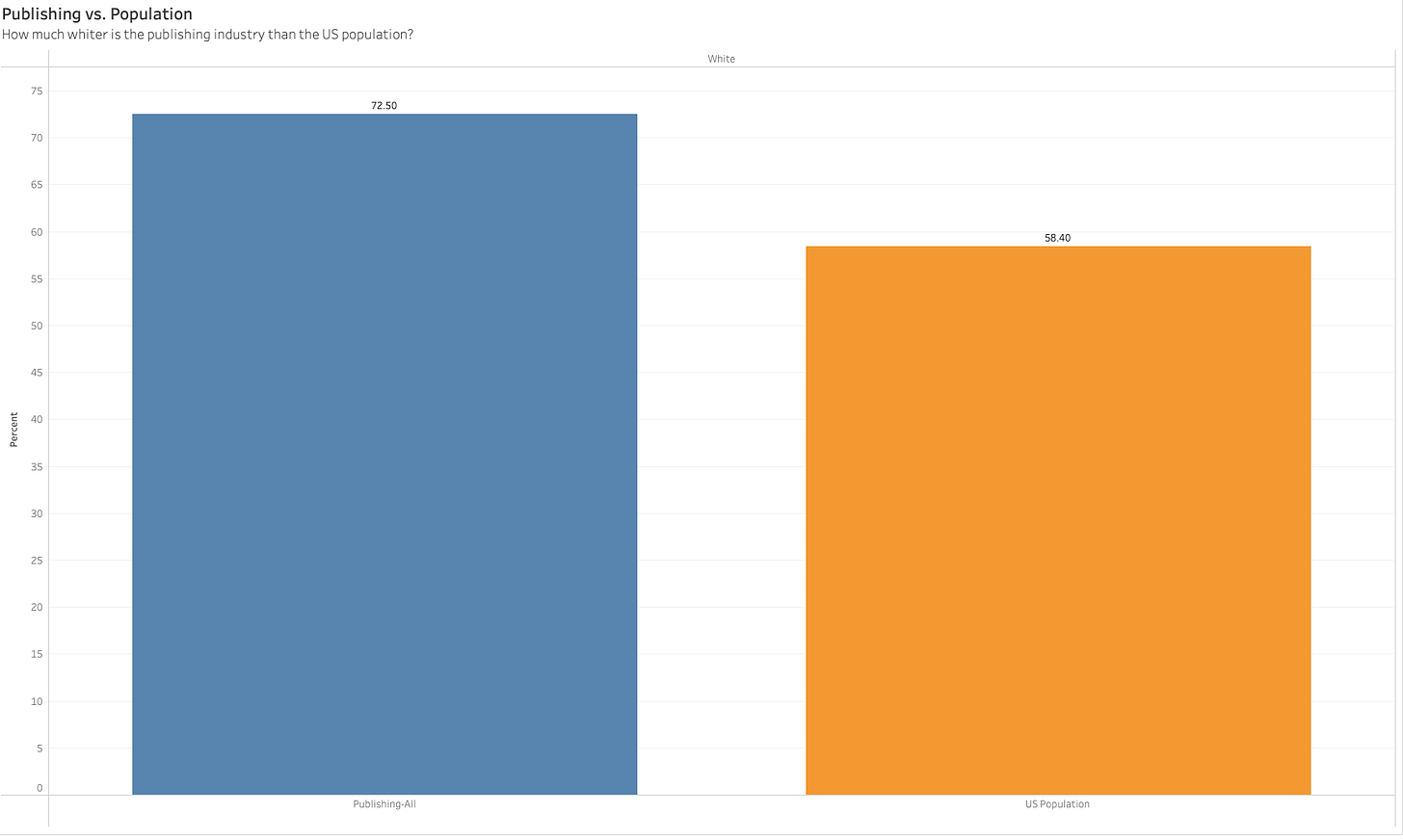

Comparison 1: the US Population

What percentage of the publishing industry self-identifies as white, compared to the United States population? This question can help us understand the difference between who is making books, and who is potentially buying books, reading books, or being read to.

The high-level takeaway: the US publishing industry is far less diverse than the United States.

Publishing is 14% whiter than the US population.2

Publishing is 21% more female than the US population.

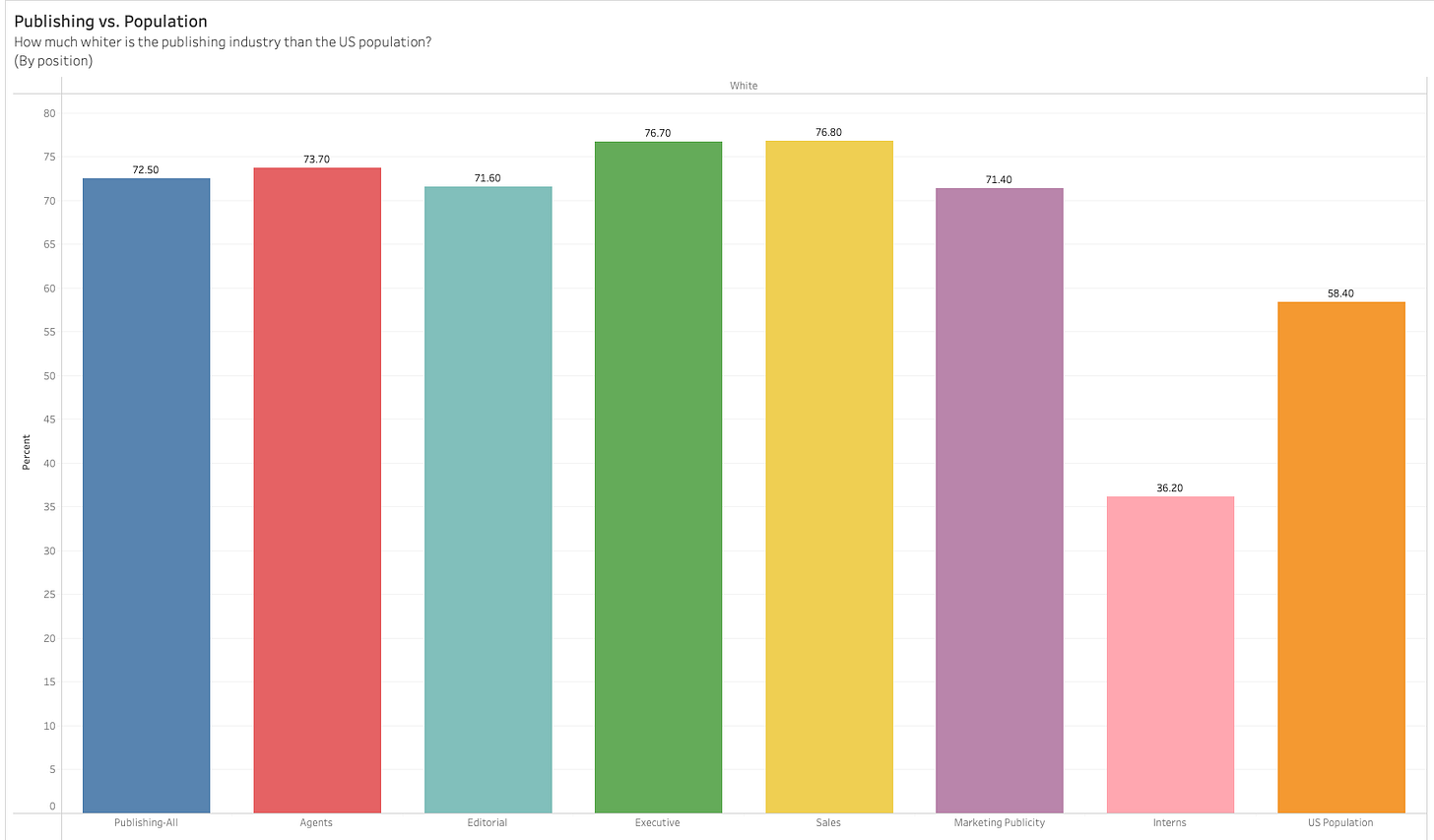

Here’s another version of the same info, broken down by position-type.

Lee & Low already discussed this in their report, which you can read here, but I want to highlight the difference between Interns and Rest of Publishing, as well as the difference between Interns and the Population. This is the most hopeful sign of change I’ve yet to see in terms of the industry’s demographic makeup.

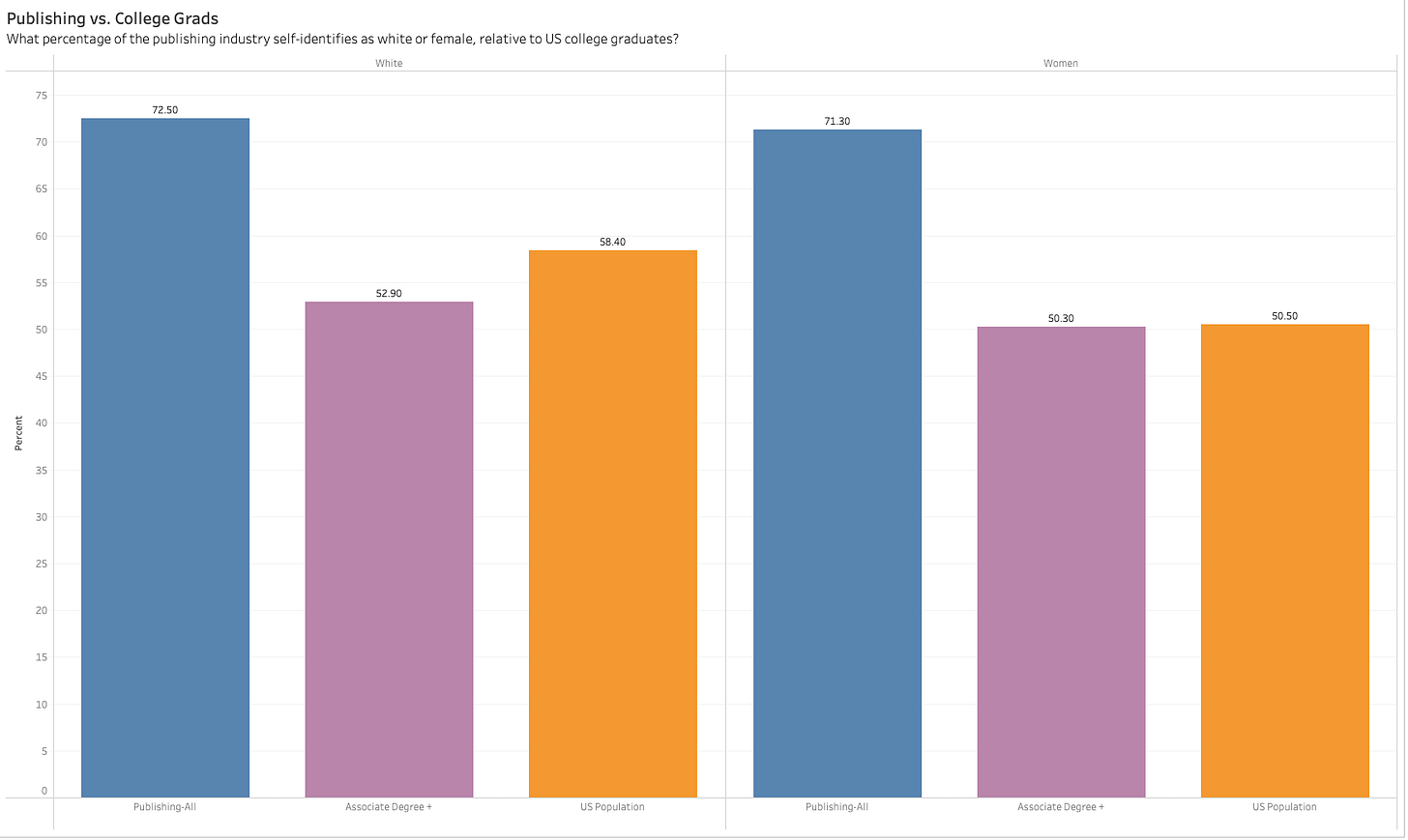

Comparison 2: College Grads

The difference between the makeup of publishing and the US population can help us understand the difference between producers and potential readers/buyers. But that’s not necessarily helping us understand how white publishing is in comparison to how diverse it could be. Obviously, I can’t know who is applying for jobs. But one data point that might help us is the pool of eligible candidates: college grads.

What percentage of the publishing industry self-identifies as white, compared to US citizens with at least an Associate Degree?3 You need a college degree to work in publishing. This question can help us understand how white publishing is compared to its pool of eligible workers. I also broke down these statistics by gender identity.

52.9% of people with at least an Associate Degree4 self-identify as white, in comparison with 72.5% of people who work in publishing. The gender difference isn’t really surprising on this point, as Associate’s Degree holders self-identify as women at the same rate as the US Population.

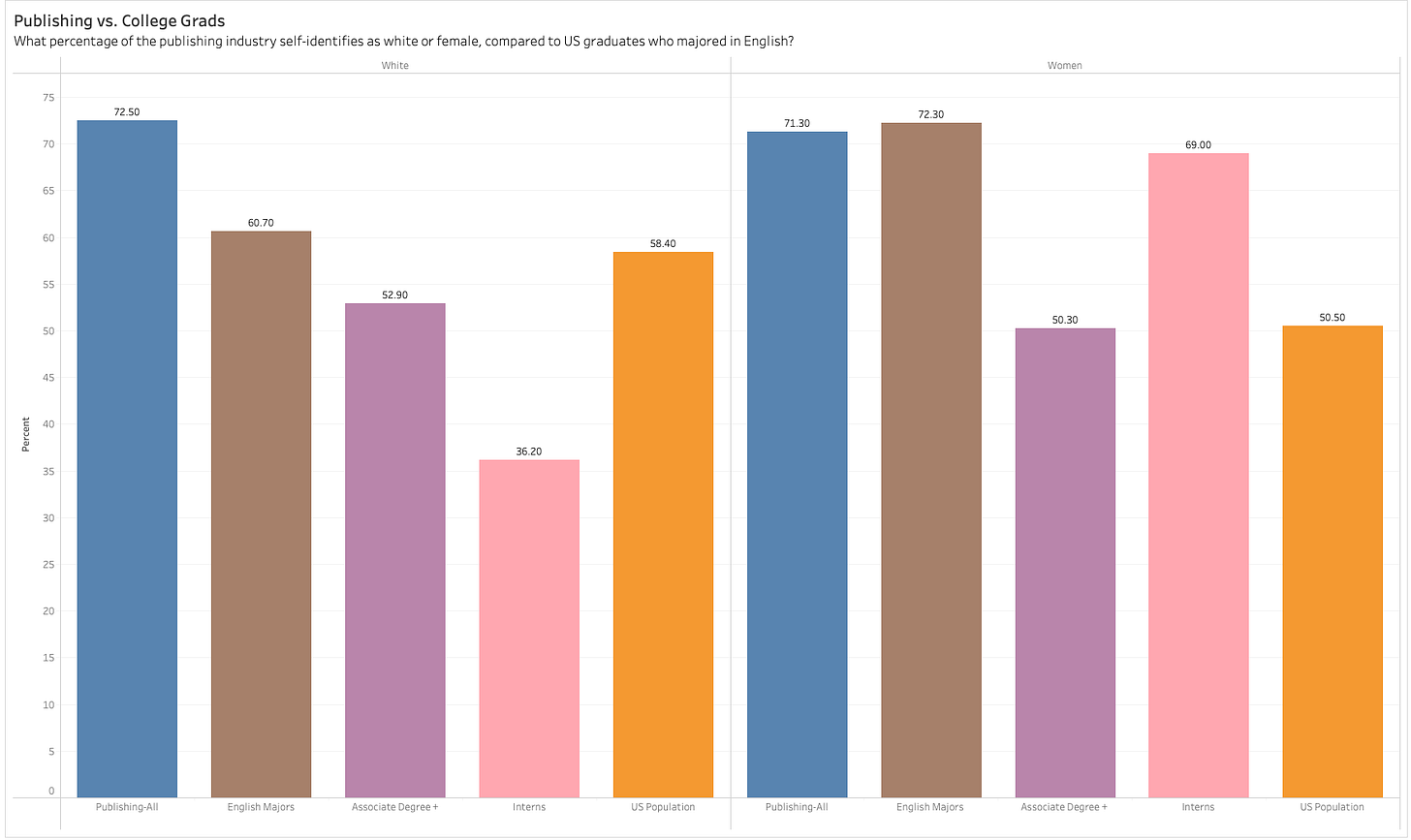

Holding a college degree may mean that you are eligible to work in publishing, but it doesn’t mean you are likely. I genuinely doubt that pre-Med majors are enrolling in the Columbia Publishing Course or that rising seniors in Physics are trying to intern PRH. Instead, we can get a better picture by turning to the industry’s largest feeder major: English. What percentage of the publishing industry self-identifies as white, compared to US college graduates with degrees in English Literature?5 This is where, for this English prof, things get interesting.

The gender makeup of the publishing industry is virtually the identical to the gender makeup of the English major. But the English major isn’t that far off from the US population: it’s 61% white, in comparison to publishing’s 73%. English majors are more diverse than I anticipated. Considered in this light, publishing is 12% whiter than its likely entry-level candidate pool.

More than the US population and more than all degree-holders, that 12% of over-representation seems the target to address. If the intern numbers are any indication (36.2% self-identify as white), then this seems to be a sign of movement in the right direction. This is the number I’ll be watching in the next Lee & Low survey.

Two things I don’t know that I’d like to know:

Which universities are these interns coming from?

How many of these internships are paid/unpaid? And, if the latter, how many of interns receive financial support from their family? From their university? For instance, Temple University, where I work, runs a grant program to compensate students who work in unpaid internships before graduation, recognizing the value of internships to eventual employment (as well as the exploitative nature of many, and the way that the reliance on internships disproportionately impacts students from low-SES backgrounds and marginalized groups).

How many of those interns are actually converting to entry-level hires? And where did those new hires go to school? I’m in the trenches with my amazing Research Assistant who’s trying to get an entry-level publishing job right now, and it is rough out there.

Comparison 3: Other Professions

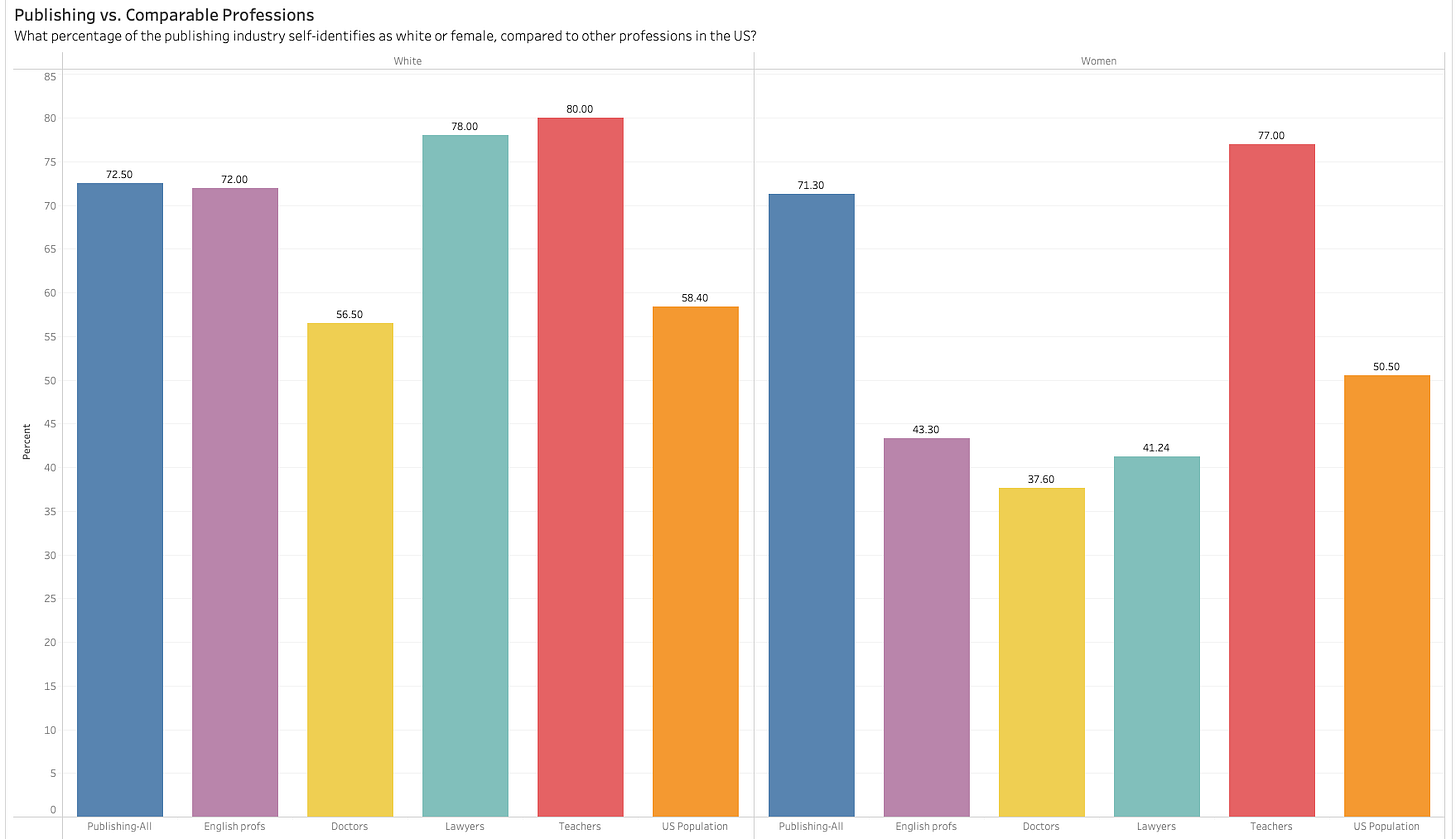

At this point, you may be asking: OK, but isn’t this simply a problem for any profession that requires a high level of literacy, a 4-year degree, or (often) a graduate degree? Great question. Turns out, most fields that meet these criteria are also interested in their demographic makeup and better reflecting the US population. I compared the makeup of publishing to a few relevant professions: law, English professors, and public school teachers. For fun, I added in doctors. What percentage of the publishing industry self-identifies as white, compared to relevant professions?6

I’m hesitant to read much into this professional data, because these industries all confront their own structural inequities. Racism and sexism manifest in different ways. But, still, publishing looks about the same as the English professoriate in terms of its whiteness. The industry isn’t as diverse as the medical field, and not quite as white as law or education. What stands out to me, though, is the gender difference.

While most all of the professions (save education) that I pulled lag behind the US population in terms of their gender balance, publishing does not. There are almost twice as many women working in publishing as there are working as physicians; publishing is around 30% more female than law and the English professoriate. And publishing is almost as female-dominated as k-12 public school teachers. It’s worth noting that neither publishing nor k-12 education require an advanced degree (beyond the BA) for an entry-level position, though many folks in both professions do have advanced degrees and teachers participate in ongoing professional development and continuing education; this certainly must account for some of the disparity. Still, this throws into relief, for me, just how female publishing is.

I’m not complaining about this last point: let’s put women in charge of everything, please. Of course, they’re not in charge of everything, exactly. The Lee & Low survey found that, while 71.3% of publishing employees are women, 62.9% at the executive level self-identify as women. In other words, relative to the industry as a whole, men are over-represented a the executive level. (And in literary history, about 99% of the scholarly attention goes to the men—Perkins, Gottlieb, Lish. All great! But how much more can we say?)

Executive level aside, the big picture over-representation of white women, in all of these data, is fascinating for many reasons—not least because white women are the demographic commonly thought to be the Average Book Buyer in the United States. (This isn’t necessarily wrong, but it’s complicated—foreshadowing!) We can’t read any sort of causality into these data (which came first, the white woman editors or the white woman readers?), but I do want to note the demographic similarity between producers and buyers.

This is the sort of post that I really like to run. It interrogates a common assumption—and that assumption isn’t wrong,publishing is very white—to establish something like ground truth. While, on the one hand, this post reasserts what we already know, it also provides points of comparison that can help solidify and strengthen arguments, all of which is more clarifying than a free-floating statistic. My hope is that these data can be more relevant, and more useful.

And, at the very least, I hope to have satisfied Reader 2.

My book is being published by Princeton University Press, and as an academic title, it is subject to a rigorous process of peer review. This means that two anonymous reviewers who are senior-ranking English professors with expertise in a relevant subject area review the book to make sure the argument is sound, well-argued, and executed properly.

Population data comes from the US Census, including all people who self-identify as “White alone, not Hispanic or Latinx.”

Educational attainment data from the American Council on Education.

This includes everyone who has an Associate’s Degree, Bachelor’s, Master’s, Doctorate, or Professional.

On degrees in English Literature: American Academy of Arts and Sciences, Humanities Indicators.

Great post! I'm enjoying this substack.

Really enjoyed reading this. At the risk of getting too personal, I graduated with a BA almost two years ago and have had no luck finding a job in publishing, even though I worked as an intern (then moved on to a "contract worker" at the same place, getting paid very very low for projects that took weeks to complete). A year ago, I decided to pave my own way as a freelance designer/typesetter, because I love doing book design. However, this path has also been very rough, filled with the ups and downs that come with starting a business (+ dealing with many publishers saying my prices are too high, even though I'm making less than minimum wage on nearly every project). I'm fortunate to have some financial backing, but it's concerning how long it's taking me to make a livable wage after graduating. And if it's been this hard for me, I'm constantly reminded of how difficult it is for those who have less privilege than I do. I appreciate your analytic look and critical analysis of the publishing industry, and it really spoke to me today.